Of the old Pauline Prime Ministers so far, The Rt Hon Sir William McMahon GCMG CH, (in College 1927-31) and The Hon Gough Whitlam AC QC (in College 1935-42), it is Whitlam who has stood out most strikingly in the Australian political discourse.

In the 1975 edition of The Pauline, another alumnus, Ted St John (in College 1934-38) wrote: “Few who knew Gough at Paul’s could have guessed his potential as a future leader — least of all, perhaps, leader of the Australian Labor Party.” [1] Ted remembered him as a much loved member of the College and an intellectual who didn’t become politically active until sometime after 1939.

In Troy Bramston’s latest biography of Gough Whitlam he describes a College event that shows Gough’s typical character of the time he was a Pauline:

Gough Whitlam first became prime minister in May 1940. Not the Australian prime minister – that role was played by Robert Menzies. Whitlam portrayed Neville Chamberlain in the St Paul’s College Revue at the University of Sydney, clad in bowler hat and holding an umbrella. He was parodying Chamberlain’s infamous return from Munich in September 1938, when he held aloft a piece of paper with Adolf Hitler’s signature and proclaimed that he had achieved ‘peace in our time’. Whitlam, however, waved a trail of toilet paper. ‘I have seen their leader and I have his reply,’ he told the audience. ‘It bears both his mark and mine.’ The skit produced sustained laughter, as Gough wrote to his parents and (sister) Freda. ‘I was a really big success as Chamberlain, although he was out of office after the first dress rehearsal.” [2]

And from Ted St John:

Gough was a College man rather than a University man during the period I knew him so well. He attended lectures at the University but his whole life and interests were centred around the College and its denizens. He did not participate in the activities of the University clubs, political or other wise. Nor do I recall him engaging in heated political debate. He certainly did not identify himself then as a Labor supporter.[3]

Despite Ted’s recollections Gough was quite involved in University life. He was elected editor of Hermes in 1939, he was associate editor of Blackacre the Law School journal 1939-41 and 45-46, he was also a member of SUDS. He was a Fellow of the University Senate 1986-89 and was also a foundation member and Visiting Fellow in the Department of Political and Social Change at ANU from 1978 to 1980, and in 1981 he became the first National Fellow based at the ANU Research School of Pacific Studies.

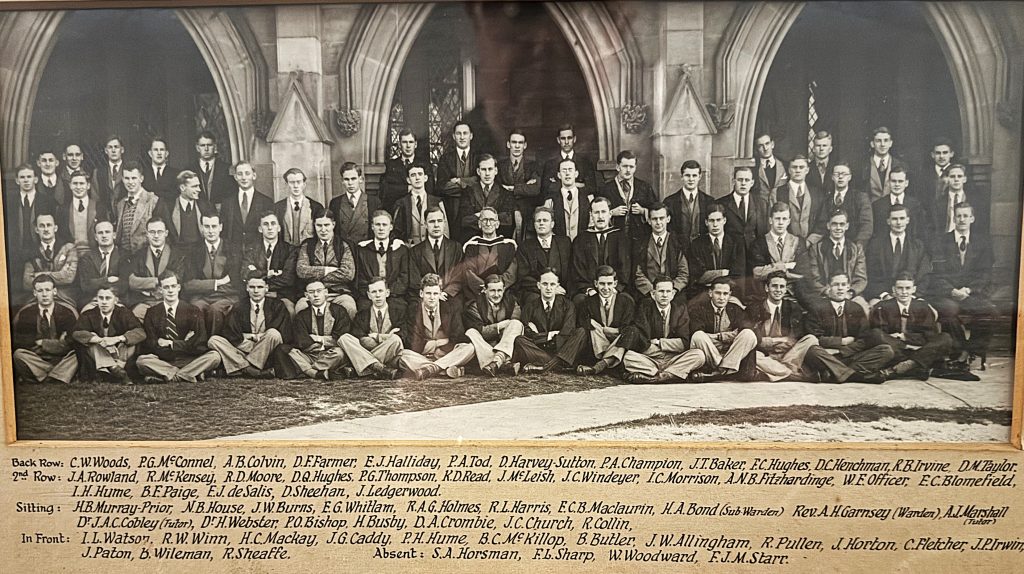

At Sydney University Gough completed BA in 1938 with a Classics major, LLB in 1946, and was made DLitt (Honoris Causa) in 1981. At St Paul’s he was Student’s Club Secretary in 1941, Senior Student in Michaelmas Term 1941, Editor of The Pauline, Chapel Warden, managed the Library, member of the Debating Team, and in the Rawson Cup Rowing Team.

He was called up for service in June 1942 joining the RAAF as a navigator in the Pacific theatres of WW2. His 1942 valete states: “His manner and attitude to life was reminiscent of Pooh-Bah…. Few men have done more for the College during their stay here. His activities were legion…” [4]

The College’s record of War Service was the work of Gough after he returned from active service to complete his Law degree and again live in College. Once he’d left College he was a regular visitor to work in the Library on the College Archives. His handwritten notes remain an important part of the collection and were ‘discovered’ by Troy Bramston during his research for the new biography. Gough was also Honorary Secretary of the St Paul’s College Union and “his administrative enthusiasm was essential to the Union’s post-war revitalisation – he continued afterwards as its “records secretary”. Finally, he was a Fellow of the College 1947-53.” [5]

After developing his interest in Law, Gough chose politics. Ted St John describes him as “a first-class Parliamentarian, of a kind quite rare in Australian politics”. From his by-election win in the seat of Werriwa for the Australian Labor Party in 1952 he spent some 20 years in Opposition. In 1960 he became Deputy Leader, and Leader of the Opposition in 1967.

Seizing the mood for change in 1972 he led the ALP to election victory under the slogan “It’s Time”. His first ministry was himself and Lance Barnard holding all appointments! After which he took a more conventional approach “and many very worthwhile and long overdue things were accomplished.” [6]

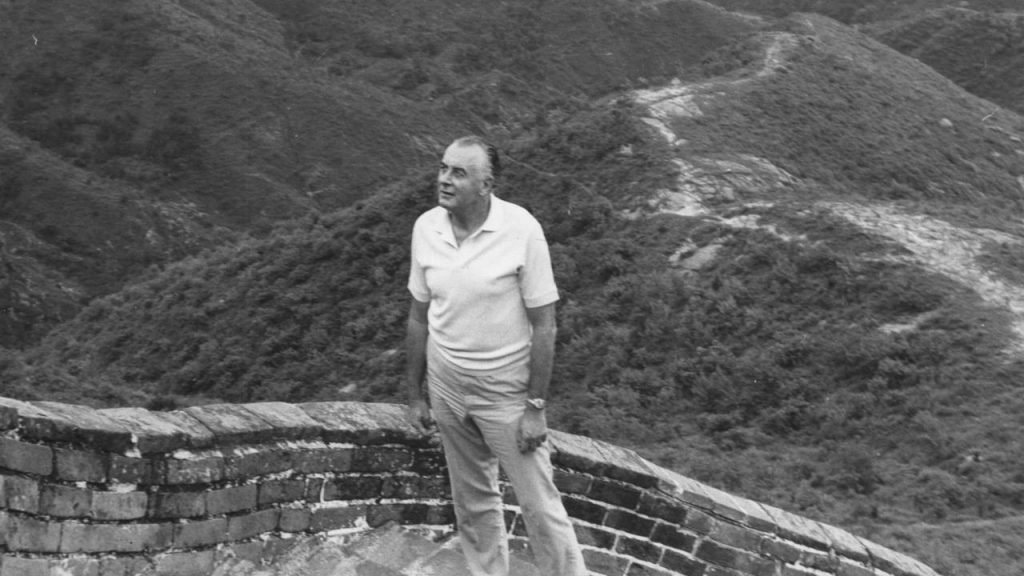

He moved to immediately withdraw Australian troops from Vietnam, recognised the People’s Republic of China, established a Department of Aboriginal Affairs, abolition of university fees, needs-based funding for government schools, the introduction of universal healthcare (now Medicare), Legal Aid, the Family Court of Australia, lowering the voting age from 21 to 18, and welfare payments to support mothers and the homeless. Other changes were the Racial Discrimination Act, Aboriginal Land Rights, the purchase of Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles, the construction of the National Gallery, establishment of the Australian Film Commission, the Australia Council (for the Arts), handing over traditional lands in NT to the Gurundji people, the first visit to China by an Australian PM[7], changed Australia’s stance on apartheid in South Africa, and the Order of Australia was established on 14 February 1975 by Elizabeth II, Queen of Australia, on the advice of prime minister Gough Whitlam.

Subterfuge, deceits, coverup and scandal led to his downfall with its beginnings in the “Loans Affair” in late 1974[8]. This gave the Opposition the ammunition to block supply in the Senate, hoping to force an election. It was when Gough refused to go to the polls that the Governor-General Sir Joh Kerr made the “explosive move” on 11 November 1975 to use his Constitutional powers to dismiss the government of the day and appoint the Leader of the Opposition, Malcolm Fraser, Caretaker Prime Minister—The Dismissal. “There is no doubt Kerr’s strategy could have been delayed and disrupted with uncertain consequences. But Labor, under Whitlam, was not prepared for such a task or able to seize the opportunities when presented.” [9]

The key to understanding the crisis lies in its dual nature: this was a struggle between men and a conflict between institutions. It is unparalleled in our history as a gladiatorial struggle between two wilful leaders. It is equally unparalleled for the pressure it applied to the principal institutions of the state – the parliament, the office of the governor-general and the High Court – and its destructive effect on the series of conventions that underwrite the consensus and stability required in a constitutional democracy. …

…Predictions that the crisis would permanently undermine our democracy have proven unfounded. [10]

Gough remained Leader of the ALP which was overwhelmingly defeated at the 13 December 1975 double-dissolution election, and stayed on as Leader of the Opposition for another two years. Afterwards he went to Paris as Australia’s Ambassador to UNESCO and with his wife Margaret were part of the successful Sydney Olympics bid team.

We cannot fail to remember that the Constitution designed the Senate to be a House of greater power than any ordinary second chamber—Rt Hon Sir Edmund Barton PC GCMG, first Prime Minister of Australia.

I don’t mind taking on a fight, and I have yet to lose one—(August 1974) The Hon Gough Whitlam AC QC, 21st Prime Minister of Australia.

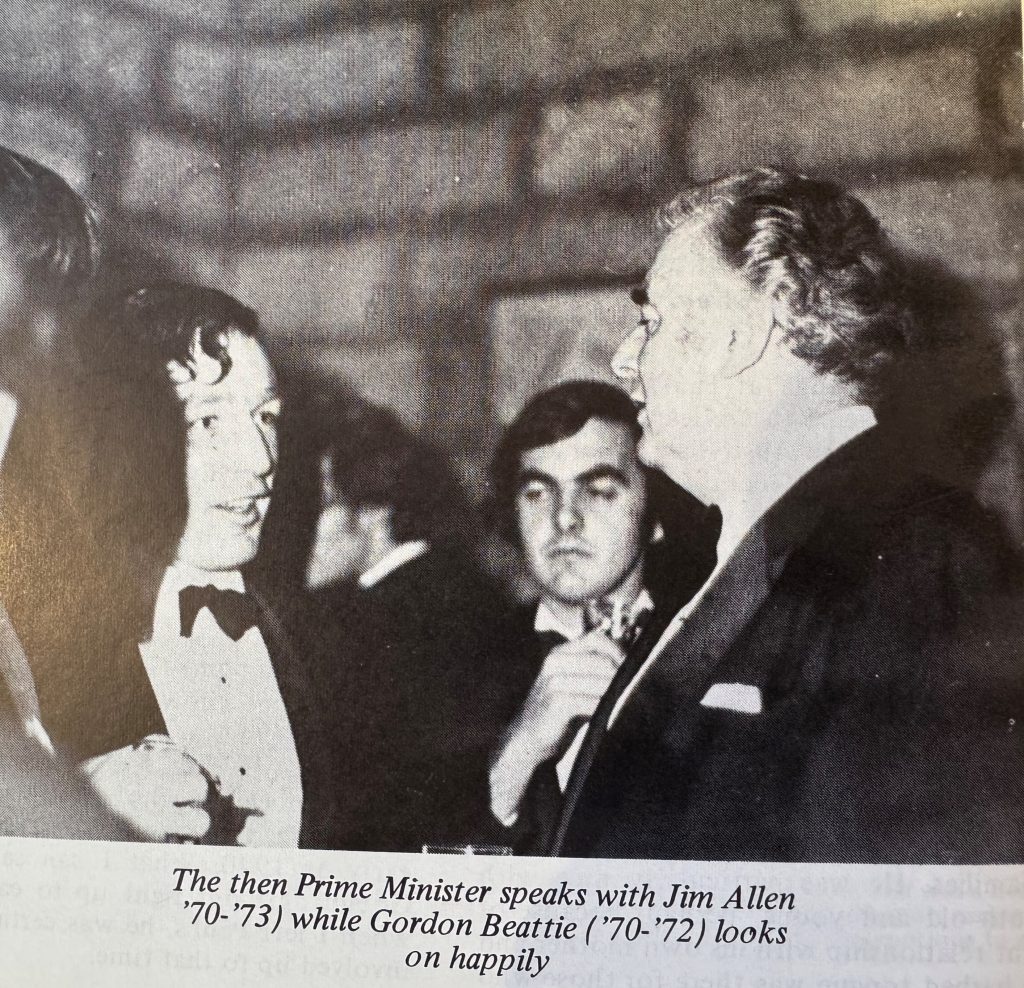

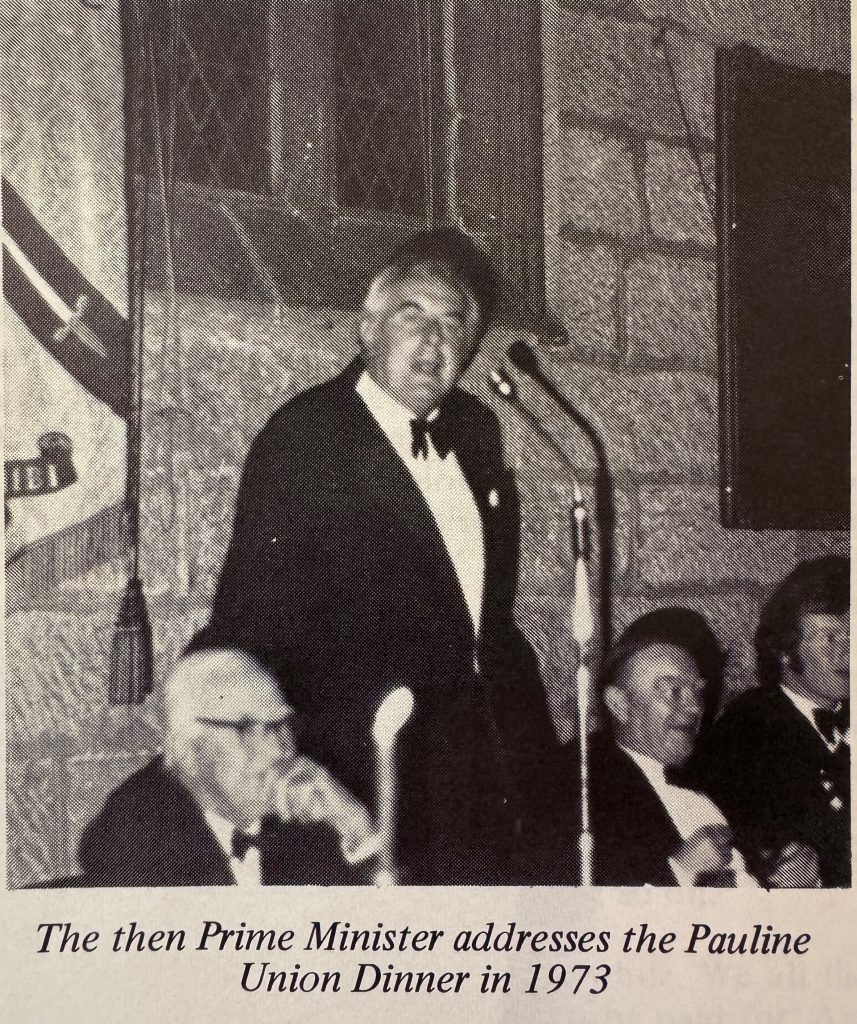

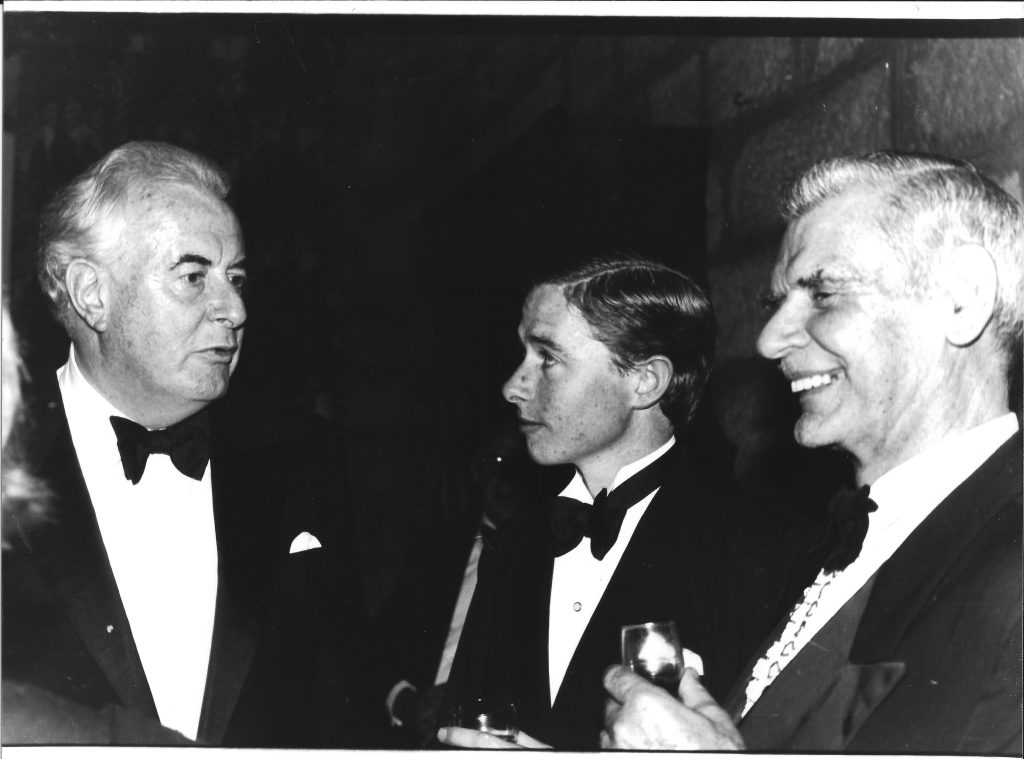

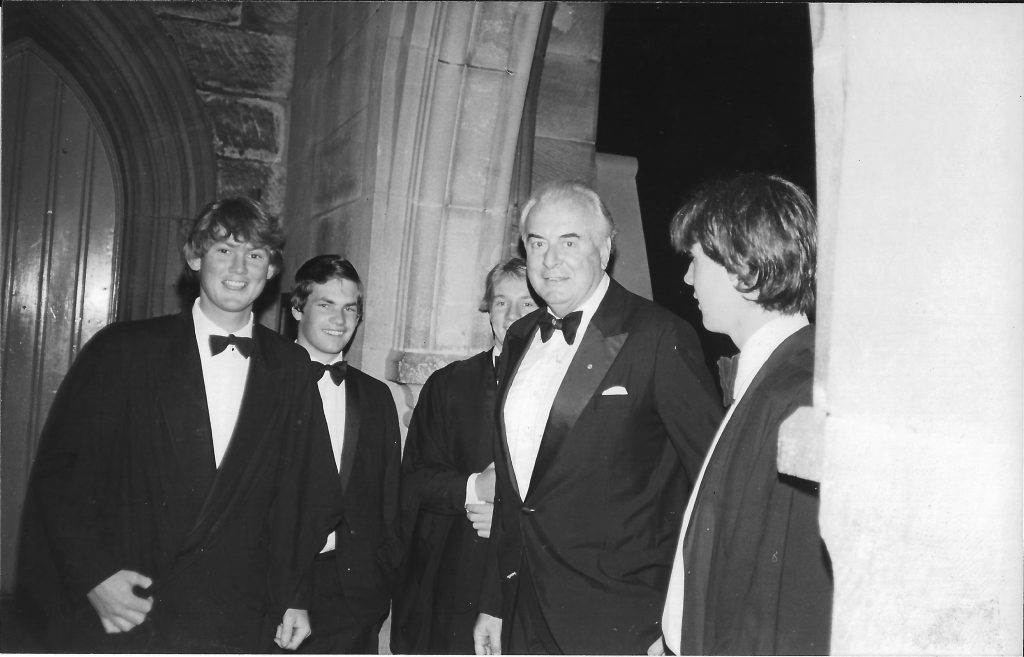

Gough Whitlam visited the College in 1973 (while PM) as Guest of Honour at the Union Dinner and again for the Union Dinner in 1982, and as guest of honour at the College’s Academic Dinner in 1989.

1982 and 1989 visits

[1] Edward St John, “Gough Whitlam as Prime Minister”, The Pauline Number 73, 1975, p. 47

[2] Troy Bramston, Gough Whitlam, the Vista of the New, 2025 Harper Collins, p.35

[3] St John, op cit, p. 48

[4] Exeunt Alunmi: ‘E.G. Whitlam BA’, The Pauline, No. 40 1942, p. 24

[5] Obituary “Edward Gough Whitlam AC QC”, The Pauline vol. CXII, 2014, p. 72

[6] St John, op cit, p. 49

[7] See: https://www.stpauls.edu.au/a-50th-anniversary-old-pauline-visits-china/ and https://www.stpauls.edu.au/pm-follows-gough-whitlams-path/

[8] As Bramston puts it: “the secret and unorthodox loan raising”, op cit, p. 456

[9] Paul Kelly and Troy Bramston, The Dismissal in the Queen’s Name, 2015 Penguin Australia, p. 247

[10] Ibid, pp. x-xi